My published papers have appeared in many different places: as chapters in books, as journal articles, as comments and reviews. In my paper “Cambodian Genocide: Ethics and Aesthetics in the Cinema of Rithy Panh” I began to interrogate the relationship between traumatic history and its representation in cinema and art. Published as Chapter 9 in a collection of essays on genocide and visual culture, I discussed issues around remembrance and reconstruction, in part through the story of Vann Nath, one of only three survivors of the notorious detention centre Tuol Sleng.

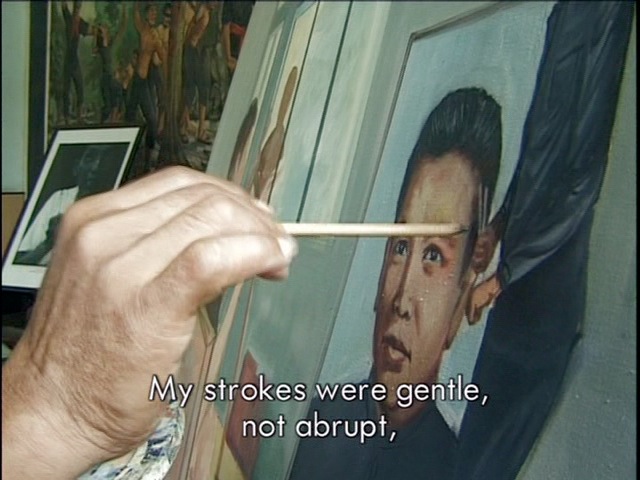

He was an artist by training and vocation. When Pol Pot discovered this, he took Vann Nath from the fetid prison cells and made him his personal portrait artist. In a wonderful section of Rithy Panh’s film Vann Nath explains to the viewer how he went about this task. Later, after 1979, he began painting his memories of S-21. This still from the film shows him gently painting the details of Pol Pot’s face. The banner still is reproduced below, along with another of Vann Nath’s most famous paintings from the post KR era.

The late Cambodian artist Vann Nath explains how he painted the portrait of Pol Pot.

Cambodian artist Vann Nath with one of his most famous paintings.

Holocaust Intersections: Genocide and Visual Culture at the New Millennium

Edited by Axel Bangert, Robert S. C. Gordon and Libby Saxton

Moving Image 4•25 September 2013

including:

|

Cambodian Genocide: Ethics and Aesthetics in the Cinema of Rithy Panh

|

https://www.academia.edu/5050954/Ethics_and_Aesthetics_in_the_Cinema_of_Rithy_Panh

Rithy Panh’s films are extraordinarily beautiful and eerily reflect on a period of profound trauma from the perspective of a survivor who was not there. This estranging temporality of reconstruction is evident in his subsequent films. They are composed of a narrative exposition based on memories of survivors, similar to the effect arising from recordings of the survivors of the Holocaust.

It is strange then to go back into the surviving pieces of original film from the Khmer Rouge era, and the issues these fragments pose. I have explored this in my recent paper Fragments in the Archive: The Khmer Rouge Years published in Plaridel, special issue on Cinema and the Archives in Southeast Asia, Volume 15, Issue 1, June 2018. Ed. Adam Knee.

Rithy Panh has been deeply engaged in the promotion of a new documentary cinema for Cambodia, which has made enormous strides in recent years in promoting the work of young filmmakers and encouraging the circulation of new interpretations and recuperations of memory.

Hamilton A, 2013, ‘Witness and recuperation: Cambodia’s new documentary cinema’, Concentric: literary and cultural studies, vol. 39, pp. 7 – 30, http://www.concentric-literature.url.tw/

A paper will appear shortly (2020) as “Haunted Screens: the Star in Cambodian Golden Age Cinema”. This paper considers the eery effects of recovering a cinema almost all of whose stars, producers, directors and artists disappeared at once but whose work and presences remain into the everyday.

Jonathon Driskell, ed. Film Stardom in Southeast Asia, Edinburgh University Press, forthcoming.